|

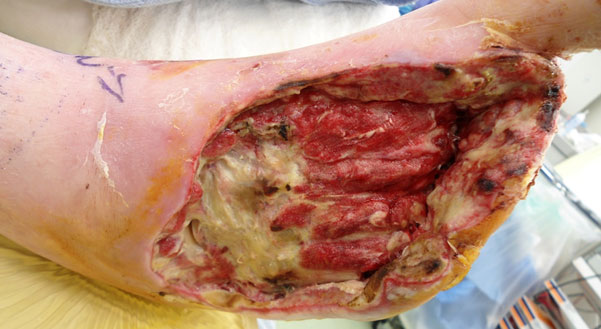

| Fig. 1. Necrotizing soft tissue infection- no gas on x-rays but note the severe cellulitis, edema, and necrotic dorsal skin. The portal of entry was in the webspace at the base of the second toe. No ischemia was present. |

|

They may or may not be sick (IDSA Grade 4 or 3), but the severity of their infection is signified by recalcitrant hyperglycemia, leukocytosis, and failure to resolve cellulitis with broad spectrum antimicrobial therapy. These important clinical clues should indicate that, very likely, surgical debridement or partial foot amputation is necessary. Several procedures are often required prior to eventual control of infection and definitive closure. (Figures 2-4)

|

| Fig. 2. Same patient after initial extensive debridement and toe amputations. Although infection somewhat improved, further necrosis and persistent cellulitis required further debridement. |

|

|

| Fig. 3. After further debridement and toe amputations, the infection came under control. A large soft tissue and osseous defect remained with residual necrosis at the midfoot, placing the limb at risk. |

|

|

|

Fig. 4. Definitive closure was obtained with a Chopart amputation.

|

|

Equally important is the necessity for detecting and treating peripheral ischemia (PAD) when present. Many patients with pre-existing PAD have a foot infection as their first presenting sign of ischemia. In the presence of neuropathy, critical limb ischemia is often silent in that the usual symptoms of claudication or rest pain are absent. Therefore, in all patients presenting with acute foot infection it is prudent to look for underlying PAD and request appropriate vascular studies and consultations. That being said, ischemia does not preclude appropriate surgical management for the acute infection. It is still essential to drain abscesses or to perform emergent local amputations to control infection. Revascularization should be performed after immediate control of infection. A final, definitive procedure such as a closed amputation or skin graft should follow the revascularization and restoration of perfusion to the foot.

We have previously discussed the management of osteomyelitis in Diabetic Footnotes Issue 18 – Osteomyelitis — Now What?, but it is worth mentioning again in the overall context of managing diabetic foot infections. I am of the (biased) opinion that in the diabetic foot, osteomyelitis is best managed surgically in most instances. While this is a matter of debate around the Globe, surgical debridement or bone resection (and sometimes local amputation) with adjunctive systemic antimicrobial therapy seems to more predictably affect a cure than treatment with just antibiotics. This is the course of treatment followed by most US surgeons until prospective studies can definitively identify those sites or patients best suited to medical therapy alone. Nonetheless, osteomyelitis very rarely, if ever, presents as an acute problem – it usually comes associated with an acute soft tissue infection.

|

Once the acute infection has been managed, the bone infection can be definitively treated as appropriate for the circumstances. For instance, in a patient with an infected plantar ulcer of a metatarsal head without gangrene, a joint resection with a 4 to 6 week course of culture-directed oral antibiotics will most often result in a “cure”.

I have not specifically addressed antimicrobial therapy thus far, because I think that we need to place a good deal of emphasis on the surgical management of limb threatening infections. Nonetheless, in our next issue, we will discuss my approach to antimicrobial management of diabetic foot infections – from a clinician’s viewpoint. I have been in the trenches for many years in this regard and have made many mistakes. Hopefully, I’ve learned from them and can offer some guidance to you as well. Until next time…

References are provided below that can expand upon many of the points made above. We welcome your opinions, concerns, and suggestions. If you have an interesting case or a troubling circumstance that you would like to share with fellow PRESENT Diabetes members, please feel free to comment on eTalk.

Best regards,

Robert Frykberg, DPM, MPH

PRESENT Editor,

Diabetic Limb Salvage

REFERENCES

- Eneroth M, Apelqvist J, Stenstrom A. Clinical characteristics and outcome in 223 diabetic patients with deep foot infections. Foot Ankle Int. Nov 1997;18(11):716-722.

- Frykberg RG. An evidence-based approach to diabetic foot infections. Am J Surg.Nov 28 2003;186(5A):44S-54S; discussion 61S-64S.

- Frykberg RG, Zgonis T, Armstrong DG, et al. Diabetic foot disorders. A clinical practice guideline (2006 revision). J Foot Ankle Surg. Sep-Oct 2006;45(5 Suppl):S1-66.

- Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Deery HG, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections. Clin Infect Dis. Oct 1 2004;39(7):885-910.

- Javier Aragón-Sánchez, Yurena Quintana-Marrero, Jose L. Lázaro-Martínez, et al: Necrotizing Soft-Tissue Infections in the Feet of Patients With Diabetes: Outcome of Surgical Treatment and Factors Associated With Limb Loss and Mortality. INT J LOW EXTREM WOUNDS 2009; 8; 141

- Javier Aragón-Sánchez: Seminar Review: A Review of the Basis of Surgical Treatment of Diabetic Foot Infections International Journal of Lower Extremity Wounds 2011 10: 33

|

|