The Challenges of Diabetic Foot Infections:

Part 1

I’ve had a particularly difficult (and frustrating) week caring for several patients with very severe diabetic foot infections. I’ve been at this for about 35 years now, but it doesn’t seem to be getting any easier. Perhaps the patients are just getting more complex and sicker or perhaps the pathogens are getting more virulent. Regardless, the infections just seem to be getting more difficult to control. While we have many more antimicrobial agents than we did years ago, antibiotics are only part of the solution to managing foot infections in the diabetic patient. We certainly need to have a very good understanding of the spectrum of coverage (and gaps in coverage) for a number of different agents. But the reality is, antibiotics alone can most often NOT be relied on to be the “magic bullet” for managing such complications. In fact, a good friend of mine who specializes in such matters is known to advocate that “draino” is the best (and perhaps the most important) agent for treating diabetic foot infections (DFI). Others can do a better job than I of discussing the multitude of antimicrobial therapies available for treating such infections (and perhaps it might be the subject of a future discussion).

|

|

Hence, I will focus here on the non-pharmacologic principles of assessment and management that are critical to success in this regard. For the purposes of our discussion, we will concentrate primarily on limb threatening (moderate or severe) infections.

The Physical Exam

A systematic and thorough evaluation is absolutely essential to detect associated abnormalities that either directly lead to the infection or contribute to its severity. Medical history and evaluation is obviously important for antecedent injuries, comorbidities such as kidney disease, peripheral arterial disease, heart disease, diabetes control and medications, allergies, etc.

A diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) is rarely caused by an infection but is perhaps the most frequent causal factor leading to diabetic foot infections. Sometimes it is just a blister or a burn (especially in the Summer heat of Arizona) or a puncture wound that breaks the skin envelope and opens the portal to infection. In the most severe presentations (necrotizing soft tissue infections) signs will include secondary blisters, bullae, or necrosis proximal to open wounds or gangrenous toes.

|

| Fig. 1. Necrotizing soft tissue infection- no gas on x-rays but note the severe cellulitis, edema, and necrotic dorsal skin. The portal of entry was in the webspace at the base of the second toe. |

Palpation of the foot might not only express purulence, but subcutaneous crepitance might be palpable as well. Ulcers of long duration or with bone exposure are at high risk for developing infections. Therefore, it is important to carefully examine such lesions – or to look for them when they might be between the toes. A sterile probe or even applicator stick can be used to examine the depths of any wounds to ascertain bone involvement or exposure or whether sinus tracts extend proximally along fascial planes or tendon sheaths. While this “probe-to-bone” test has been maligned as a good indicator for osteomyelitis, in hospitalized patients with severe infections, it actually has quite good predictive value for osteomyelitis. It is therefore a routine and essential part of my examination.

|

While many, if not most, of hospitalized patients with DFIs have at least some degree of peripheral neuropathy and sensory loss, you must always look for underlying ischemia. I am quite impressed with the frequency of undetected peripheral arterial disease (PAD) that we first diagnose upon presentation with a rather severe DFI. Perhaps the frequency of neuroischemic wounds has risen over the years; certainly the number of foot infections in such patients has in my clinical practice. Hence, palpation of pulses (at least from the Popliteal to pedal arteries) is a key part of the examination as well. Too often, however, the foot is so swollen that pulses- even when present- are difficult to palpate. This is why I carry a Doppler ultrasound unit in my pocket. I will routinely ascertain the presence and quality of Doppler signals in the pedal vessels. While rarely finding triphasic signals in the affected feet, we will often find biphasic or monophasic signals in the dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial arteries. Monophasic signals portend peripheral arterial disease, although when intermetatarsal artery signals are present, there is less concern for critical ischemia. Nonetheless, we very liberally order Doppler Segmental Limb Pressures and ankle-brachial indices (ABI) or toe pressures for qualitative and quantitative evidence of peripheral perfusion. Pulse volume recordings (PVR) are also quite useful in this regard, especially in the presence of calcified arteries in this patient population. Vascular surgical consultation to assess the need for angiography and revascularization is necessary when significant abnormalities are found.

Imaging

|

|

X-rays, of course, must be taken to determine whether there are underlying foreign bodies, deformities (Charcot), or signs of osteomyelitis. Equally important, one must always look for the presence of subcutaneous gas. Necrotizing soft tissue infections, whether caused by anaerobes, gram negative bacilli, staphylococci, or Beta-hemolytic streptococci frequently demonstrate gas accumulations around and proximal to the original focus of infections. Accordingly, plain films of the leg must also be taken to ensure that the foot infection does not involve these fascial planes or tendon sheaths. There are obvious treatment implications –emergent treatment implications- when gas is found in the soft tissues. But air is not gas in this sense of the word- sometimes air is found in the periwound area from walking on the foot. This is called emphysema and this is really not an emergency. When undrained abscesses or osteomyelitis are suspected, MRI or other advanced imaging can assist in making the diagnosis.

|

| Fig. 2. Note the soft tissue defect adjacent to the first MTP joint and the gas at the lateral ankle in this other patient. |

|

|

Laboratory Studies

Laboratory studies are, of course, critical in determining the patients’ response to the infection and help determine its severity. While complete blood count (CBC), differential, serum glucose, glycohemoglobin, and sedimentation rate are routine labs in this scenario, one must recognize that leukocytosis does not always accompany a moderate or severe infection in the diabetic patient. Hence, the clinician cannot be lulled into a false sense of comfort upon not finding an elevated white blood count (or elevated temperature for that matter). Suspicion and caution are the best attributes of the provider caring for such patients. Routine assessment of renal function is also necessary, following serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen, and estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR). These values will obviously affect antimicrobial dosing as well as consideration for angiography and contrast for MRI studies.

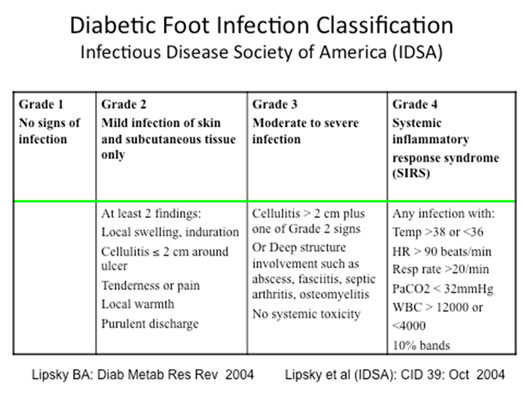

Classification

Once the patient assessment has been completed, classification of the infection will be helpful in guiding treatment. The Infectious Disease Society of America (IDSA) has put forth a DFI Classification scheme that has been almost universally adopted here and abroad. (See Table below) This scheme is an expansion of the former non-limb threatening/ limb threatening classification used several decades ago.

|

The reader is referred to the references below for an in-depth review of the points discussed in this month’s ezine. Next month, in Part II, we will discuss treatment of the infected diabetic foot. As always, your comments are always appreciated and encouraged.

References are provided below that can expand upon many of the points made above. We welcome your opinions, concerns, and suggestions. If you have an interesting case or a troubling circumstance that you would like to share with fellow PRESENT Diabetes members, please feel free to comment on eTalk.

Best regards,

Robert Frykberg, DPM, MPH

PRESENT Editor,

Diabetic Limb Salvage

REFERENCES

- Eneroth M, Apelqvist J, Stenstrom A. Clinical characteristics and outcome in 223 diabetic patients with deep foot infections. Foot Ankle Int. Nov 1997;18(11):716-722.

- Frykberg RG. An evidence-based approach to diabetic foot infections. Am J Surg. Nov 28 2003;186(5A):44S-54S; discussion 61S-64S.

- Frykberg RG, Zgonis T, Armstrong DG, et al. Diabetic foot disorders. A clinical practice guideline (2006 revision). J Foot Ankle Surg. Sep-Oct 2006;45(5 Suppl):S1-66.

- Lipsky BA, Berendt AR, Deery HG, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of diabetic foot infections.Clin Infect Dis. Oct 1 2004;39(7):885-910.

- Caputo GM, Cavanagh PR, Ulbrecht JS, Gibbons GW, Karchmer AW. Assessment and management of foot disease in patients with diabetes. N Engl J Med. Sep 29 1994;331(13):854-860.

- Grayson ML, Balaugh K, Levin E, Karchmer AW. Probing to bone in infected pedal ulcers. A clinical sign of underlying osteomyelitis in diabetic patients. J Am Med Assoc.1995;273(9):721-723.

- Lavery LA, Armstrong DG, Wunderlich RP, Mohler MJ, Wendel CS, Lipsky BA. Risk factors for foot infections in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. Jun 2006;29(6):1288-1293.

|

|