- Charcot

-

by tmi

Understanding the Etiology of the

Diabetic Charcot Foot

In FootNotes Issue 12, we discussed a very important and potentially limb-threatening complication of diabetes – the Charcot Foot. Having just returned from an International Consensus Conference in Paris dealing with this entity, and having visited the Charcot Library at La Salpetriere, I feel compelled to discuss its etiology and diagnosis in a little more depth than most readers might be familiar with. While we focused on appropriate treatments last time, it is equally important to fully understand the underlying pathophysiology – the process behind the deformity.

This rare complication of diabetes ultimately has peripheral neuropathy as it’s primary predisposing risk factor. In fact, neuropathy must be considered the sine qua non for the development of this very destructive bone and joint disorder. While Charcot first described his findings of the “arthropathies of locomotor ataxia” in patients with tabes dorsalis (syphilis), we now recognize diabetes to be the most common disease with which this entity is associated. More specifically, it is associated with patients who have long standing diabetic peripheral neuropathy. Despite this, we know that peripheral neuropathy resulting from any disease can potentially predispose that extremity to the development of a “Charcot joint”. Aside from diabetes and tabes dorsalis, leprosy and alcoholism are two of the more common diseases having been associated with Charcot arthropathy of the lower extremities. In the upper extremity, syringomyelia might be the most notable potential disease associated with the condition. Nonetheless, neuropathy alone does not cause Charcot arthropathy. Trauma, either a minor occult injury, prior foot surgery, or a significant traumatic event such as an ankle fracture, is usually the precipitating event leading to the gradual breakdown of the architecture of the foot. Unfortunately, due to the insensitivity present, a definite history of trauma (especially minor injury) cannot be determined in most cases. The diminished sensation of pain (or total insensitivity) allows the patient to continue walking on the injured foot, thus promoting further injury. In essence, a “vicious cycle” of initial injury followed by repetitive injury and further deterioration is created. As might be expected, this results in swelling, erythema, deformity, and acute inflammation in the initial stages of this arthropathy. In fact, it is the acute inflammation without commensurate degrees of pain that most often characterize the initial presentation of such patients. Classically considered painless, most current reports indicate that pain is usually present in the acute stage, but much less than would be expected for the degree of injury noted on radiographs.

|

“…it is the acute inflammation without commensurate degrees of pain that most often characterize the initial presentation of such patients.”

|

|

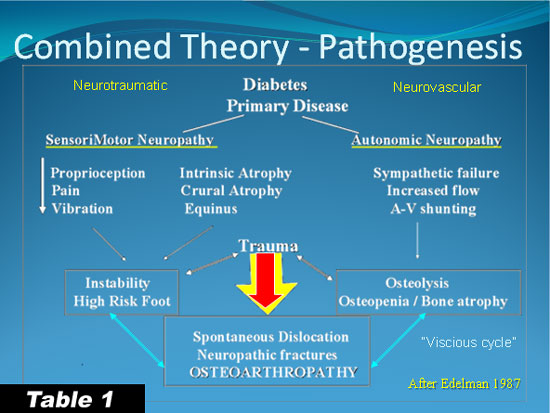

The foregoing is the simplified version of the pathogenesis of the Charcot foot, but there are several theories regarding the etiology of the condition. In addition to the neurotraumatic theory described above, the neurovascular theory has at its core a primary role for autonomic neuropathy and commensurate osteopenia or osteoporosis. The weakened bone would naturally be more susceptible to fracture, dislocation, and osteolysis even from normal degrees of stress. More likely, it is a combination of these two manifestations of neuropathy that predispose to the acute development of Charcot arthropathy after even the subtle trauma of a minor ankle sprain (see table 1).

|

In the last decade or so, much has been learned about bone physiology and the signaling systems leading to bone resorption and deposition. Although an in-depth discussion is beyond the scope of this article, the reader must become familiar with the RANKL/ OPG counterbalancing system that regulates osteoclastogenesis in normal and abnormal states of bone physiology. In states characterized by excessive bone lysis or even osteoporosis, an over expression of RANKL leads to an increase in the maturation and proliferation of osteoclasts. Osteoprotegerin (OPG), acting as a decoy receptor for the RANKL, normally will bind with excessive RANKL to mitigate its effects on osteoclastogenesis. Hence, there is normally a fine regulation on bone destruction and production. It is believed that those patients developing Charcot changes characterized by excessive bone lysis and osteopenia, there is a dysregulation of the RANKL/OPG ratio (with an excess production of RANKL above and beyond that which can be balanced by OPG). Recent evidence indicates that there is likely a genetic variation in these patients compared to those who heal their fractures and injuries normally. Perhaps this can explain why the Charcot foot occurs in less than one percent of the entire diabetes population and in only about one-third of those with neuropathy. Not all neuropathic patients go on to develop Charcot foot deformities after a fracture or minor injury. Most go on to heal uneventfully. However, it is that, as of yet, ill defined subgroup of diabetic neuropathic patients who might go on to develop Charcot arthropathy that gives us pause whenever we are faced with patients as described above. Since we have no diagnostic markers nor definitive lab tests as of yet to determine susceptible patients, we must treat all injured neuropathic patients with great caution and a high index of suspicion for Charcot arthropathy.

|

“Charcot foot occurs in less than one percent of the entire diabetes population and in only about one-third of those with neuropathy.”

|

The diagnosis of the acute Charcot foot is therefore a critical one and one that needs to be made at the initial patient presentation if we are to prevent the gross deformities typical of the chronic Charcot foot. This will be the subject of our next FootNotes e-zine. In the meantime, I have listed some general references below that will provide you with more detail on the natural history and pathophysiology of the Diabetic Charcot Foot.

References are provided below that can expand upon many of the points made above. We welcome your opinions, concerns, and suggestions. If you have an interesting case or a troubling circumstance that you would like to share with fellow PRESENT Diabetes members, please feel free to comment on eTalk.

Best regards,

Robert Frykberg, DPM, MPH

PRESENT Editor,

Diabetic Limb Salvage

REFERENCES

![]()

|