- Charcot

-

by tmi

Charcot Neuroarthropathy

Case Study, Part 2

Jeffrey Siegel, DPM, FACFAS, DABPO

Adjunct Assistant Professor, Depts. Of Medicine and Surgery, TUSPM

Impression:

- Abscess with probable cuboid Osteomyelitis.

- Severe right foot deformity, secondary to Acute Chronic Charcot Neuroarthropathy.

- Convex calcaneal valgus deformity w/Equinus.

- Diabetes mellitus, Type II w/peripheral neuropathy manifestations, unknown control.

- Hypothyroidism, stable

- Anemia, stable

- Cardiac arrhythmias, stable

- Acute and Chronic Charcot Neuroarthropathy

Plan: I had a very long discussion with Mrs. B and her husband regarding the progression and natural history of her particular Charcot foot deformity. We discussed at length that when all is said and done, she could still lose her leg. She reiterated that she doesn’t want a primary leg amputation and is willing to do what ever it takes to at least try to save her leg. “If I can survive WW II, I can survive this!” “Let’s get to it!” With that, I recommended hospital admission today, Jones compression dressing, rest and elevation while we wait for medical and cardiology clearance and a trip to the OR tomorrow. Since she is afebrile and not septic, a decision to withhold antibiotics until bone cultures could be obtained was made by ID.

Admission labs were as follows:

WBC-8.2, RBC-3.35, H/H-9.8 gm/30%, PLTS-515

DIFF: PMN-77/LYMPH-13.3/MONOS-1.9

COAG: PT/PTINR-14.5/1.27 PTT-36.8

ESR- 50mm

Chemistry: FBS-115/BUN-22/NA-139/K-4.2/

Cultures:

Blood: NG after 72 hrs

Aerobic/Anaerobic/ AFB and Fungal Cultures (in office seroma aspirate) – MSSA

Bone biopsy cuboid and culture – Acute Osteomyelitis/MSSA. Etiology: extension from dorsal seroma.

Surgical Plan:

Patient was taken to the OR for phase one of her limb salvage process: debridement of cuboid w/Bone Bx and Culture, a 6L wash-out and placement of Vancomycin and Gentamycin impregnated PMMA beads. IV Zosyn and vancomycin were then started intra-operatively by the anesthesiologist. The lower extremity was then re-draped, gowns and gloves were changed and new instruments were used for the following procedures: Achilles tendon percutaneous lengthening and percutaneous placement of an Ilizarov circular frame.

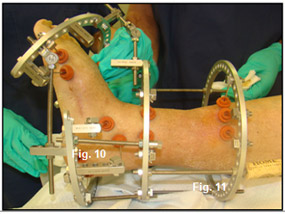

Next, the tibial block (Figure 9) was placed on her leg followed by completion of a percutaneous TAL (Figure 10). The next step in patient’s Ilizarov frame construction was placement of the calcaneal half ring. The stability of this part of the frame is very important as it will serve as a base for the forefoot half-ring to push off of. The forefoot half ring is placed perpendicular to the deformity just distal to the Center of Rotational angulation (C.O.R.A.). The ring is connected to the tibial block by a hinged connector (Figure 11)

|

|

The final component will be attaching medial and lateral 6 inch threaded rods. This will allow gradual distraction and lengthening of the soft-tissues which will ultimately facilitate manipulation and closed reduction of the C.O.R.A. and placement of the beam fixation planned in stage two.

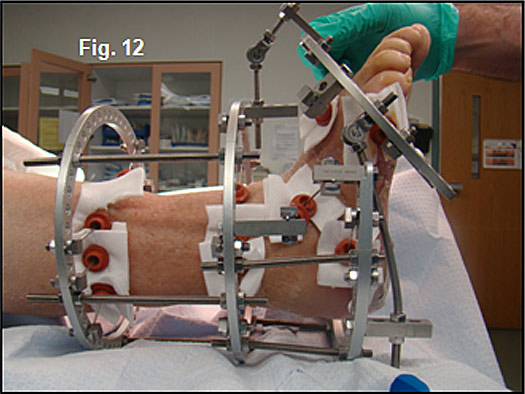

Because of profound neuropathy, the distraction process in Charcot patients can be accelerated at a rate of 2-3 mm per day (Figure 12).

|

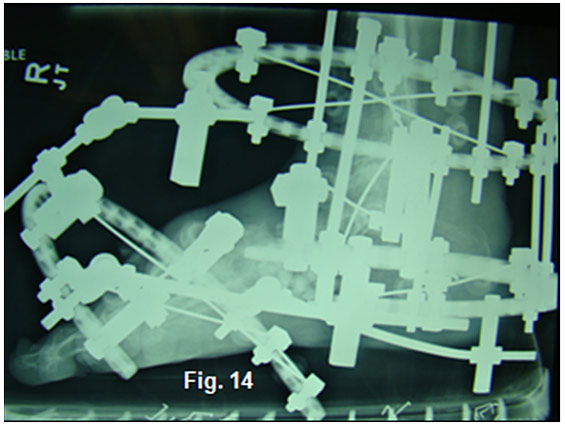

Notice the bending of the threaded rods as they distract and stretch the soft-tissues. Skin and vascular status were monitored daily during the distraction period. Rubber stoppers are used to hold silver impregnated dressing sponges in place during the 8-10 week partial-weight bearing fixation period. Radiographs confirmed placement of the PMMA beads and the distraction at Lisfranc’s joint (Figure 13,14).

|

|

Mrs. B received a one time dose of Aredia 90mg, used calcitonin nasal spray BID during her convalescence and takes Vit. D3 and Calcium 1gm daily.

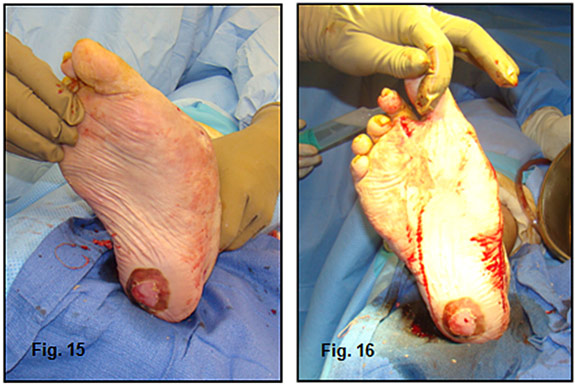

Phase two of the limb salvage process involved removal of the fixator, all but three of the PMMA beads (kept in as a spacer) and manipulation of the foot into a plantigrade position (Figure 15,16).

|

Once in place, percutaneous placements of cannulated 80-100mm intramedullary beam screws were inserted in the midfoot. The midtarsal joint was rigid and it was impossible to manipulate the hindfoot in-line with Lisfranc’s joint. (Figure 17,18). A short leg fiberglass cast was worn for 3 weeks, a CROW walker was used for 3 months and a custom molded shoe with double upright brace will be worn for a year and the braces will be removed. Clinically, her foot has a slight skewfoot appearance but in a rectus position (Figure 19, 20) and her gait is stable (See video gait).

Discussion:

Charcot Neuroarthropathy represents one for the greatest risk for lower extremity amputation that challenges our diabetic patients. Non-weight bearing is the only known cure and traditional treatments have consisted of immobilization of the leg regardless of the severity of the fracture/dislocation “as is” and strict NWB. Once the acute edema and erythema of E1 (Eichenholtz stage 1) resolve, they are placed into a CROW or TCC for three months until stage E2 and then into a custom molded shoe (E2/3). When plantar wounds developed, and months of wound care and off-loading failed, an exostectomy was performed. Twenty years ago when I was a resident, that was as aggressive as it got. Fast forwarding to today, we spend hours training our residents to perform complex 5 hour reconstructive arthrodesing procedures with or without a rotational flap. Our procedures are not always successful. With big procedures come big problems: wound dehiscence, infection and amputation – the one end result we were trying to prevent in the first place. Or in two years the patient dies, not due to the surgery, but don’t forget these people are sick, despite obtaining medical clearance with their >5 co-morbidities. Need I forget to mention the hundreds of hours of worry, lost sleep, significant lack of fair reimbursements and the excessive exposure of your practice to litigation. So why do I do this? So when is enough, enough? This was the question posed by Dr. Shapiro that he addressed in a previous article and provided the motivation to write this case study.

What we can do is offer bonafied hope to a select number of patients when all their score cards read zero in an attempt to save their leg. This, in the world of the Podiatric foot and ankle surgeon, is everything. And that is why I do this type of work….and I know I am not alone!

Unfortunately, we have “many” obstacles that wage battle with our altruistic goals: patient and family compliance, obesity, retinopathy, neuropathy, psychosis, economics, nutrition/glucose control, upper body strength, balance, home environment, etc. etc. So, when patients are told point blank that “you need an amputation”, some of these patients accept their fate, while others manage to find their way to your office for hope. It is critical that Podiatric foot and ankle surgeons are completely transparent with the patient and family regarding the fact that “high risk surgery can lead to high risk complications” and home life with a “cage”. In my practice, these are the patients who share with me, “I hear what you are saying, BUT if there is even a 10% chance of saving my leg, please try.” What would you do in their situation ?

Let Us Consider the Decision for Mr. B

That brings us to our case study: Mrs. B. is a 78 y/o grandmother who presented with a midfoot Charcot deformity, dorsal foot abscess/seroma with secondary cuboid osteomyelitis, doomed for amputation. Traditional medicine would have us debride the cuboid, wash out, place antibiotic beads or fashion an antibiotic cuboid spacer, IV antibiotics for 6 weeks, and immobilization. If after negative bone biopsy, cultures and normalization of the CRP, we either take her back to the OR, harvest bone from her hip, create two long incisions for an arthrodesis, and start 3-4 months NWB OR just leave it alone and wait for the recurrent midfoot ulceration and probable amputation.

Mrs. B. is 78 years old! I recommended another option: closed reduction with external fixation (CREF) and gradual distraction, while simultaneously addressing the osteomyelitis. The frame was not pre-assembled. While this procedure complies with the traditional paradigm, CREF w/gradual distraction is best indicated for patients in the acute/semi-acute Charcot setting. In sedentary or elderly patients, this modality can accurately address the deformity without incisions and still yield a stable, deformity-free rectus foot. If there are open wounds or bone infection as in this patient, the frame can be custom built to avoid the problem areas, allow placement of a VAC in case of wounds and still aggressively treat the deformity. Once edema and erythema (E1) resolve, partial weight bearing can be instituted. So, rather than accepting the deformity “as is”, CREF can correct the problem while respecting the soft-tissue and osseous structures need to rest, heal and consolidate (beginning of E2). Three weeks following the beaming (now into Stage E2), patients are then placed in their CROW in the same timeframe as with traditional approaches to Charcot treatment.

In stage two, the frame was removed, the deformity manually reduced and IM beams percutaneously placed through the 1st and 2nd TMT joints. The midtarsal joint was rigid and not reducible so the hindfoot was not beamed. There was no cuboid so the lateral column was not beamed. Plus, although her labs documented resolution of her bone infection and her foot was clinically stable (no edema, erythema and normalization of skin temperature), I had serious concerns regarding the existence of walled-off pockets of chronic osteomyelitis and did not want to place hardware in the area. I also was concerned regarding instability, so Mrs. B agreed never to walk barefoot (except for the video).

No matter how we treat our Charcot patients, the ultimate goals are to provide a stable, plantigrade foot, remove as much of the deformity as possible so that the extremity can be braced. In select patients, when CREF with distraction is followed by a beaming procedure, the gap between accepting the deformed foot “as-is” and do nothing vs. major reconstructive surgery and months of non-weight bearing can be bridged with much less risk.

|

###

|

Commentary by Robert Frykberg, DPM, MPH & PRESENT Podiatry Editor, Limb Salvage:

| I applaud Dr Siegel for his efforts to think “out of the box” to address this lady’s concerns regarding a very serious, although rare complication of diabetes. The Diabetic Charcot Foot is indeed a clinical conundrum that most podiatric physicians have to manage on a fairly frequent basis. It is indeed a potentially limb-threatening complication, especially in cases further complicated by recurrent foot ulcerations. There is literally an explosion of new literature in the podiatric, surgical, and medical disciplines concerning this entity in terms of underlying pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. While once considered “taboo”, surgical management of the Charcot foot has become progressively more commonplace over the last two decades. We frequently see case series or case reports of sometimes novel approaches to the operative reconstruction of neuropathic foot deformities. While certainly not novel, this case adds another to a long list of case reports in the literature. Nonetheless, we have few randomized controlled trials to guide us in this regard (only for medical or non-surgical treatments) and several prospective case series (cohort studies involving single cohorts of surgical patients). Hence, most of our decisions are based on retrospective cohort studies, case series, or case reports. This begs a long series of questions that I know Dr. Siegel asked himself before granting this patients request for operative treatment, and I, as devil’s advocate and educator, must bring to your attention “What is the long term benefit of our approach and are we improving the patient’s quality of life by operating on them”? Was this patient’s limb truly “at risk” when the surgery was performed? How do we know that this patient (or any other for that matter) is better served by operative intervention or by conservative management? Where is the evidence to substantiate our position? Where are the comparative effectiveness trials to ascertain which patients (and deformities) are best served by surgery and which are best treated conservatively? Knowing full well that neuropathy and external fixation impart an independent 4-fold and 3-fold risk for postoperative infection (Wukich et al. 2010), should we not take this into consideration when deciding to operate on such complicated patients? Would we do a complex flatfoot reconstruction on a healthy 78 year old woman? When is enough surgery enough? This woman had her deformity for 6 months preoperatively, but is relegated to at least 1.5 years of surgical recuperation before she can ambulate without braces (provided no complications ensue). How do we know that a CROW brace and subsequent molded show would not suffice in the long term for her? She seemed to have a plantigrade foot without plantar ulcerations at the time of presentation. Has the surgery made her better off in the long run? (We do not have a long term follow up at this point) Will she survive long enough to regain her independent mobility? Has her osteomyelitis been “cured”? Everything is wonderful when the surgery works out well, but I worry about potential complications (i.e., MI, DVT, PE, Pin Tract infections, Osteomyelitis, etc.). Hence the need for evidence to support our approach to patients, both in general and at the patient level. Surgical approaches to the Charcot foot have indeed corrected thousands of deformities and saved many limbs from amputation to be sure. This is a good thing. New approaches need to be considered, but carefully considered based on specific patient characteristics and surgical criteria (much of which is currently lacking). So the question as to when or when not to operate looms before us all. Is this a condition looking for a surgical technique or do we have techniques looking to be applied to this condition? The answer will always fall back on the premise that we do what is best for the patient in the given circumstances. Caution should rule the day with these very complicated patients – often with underlying cardiac dysfunction, autonomic neuropathy, morbid obesity, and renal insufficiency. But we must face the realities of our current predicament: there is little high level comparative evidence to support our positions. Damned if we do and damned if we don’t. I hope this editorializing will not discourage the reader from entertaining surgical options for the Charcot foot- it is meant to serve as a reminder of the complexity of not only the patients, but also of some of our procedures. And primarily, we are looking to generate discussions on this very difficult subject. I expect many of you to disagree with me, while many more seasoned practitioners might very well have the same precautionary approach that I advocate. An eTalk discussion has already begun on the PRESENT Podiatry website. Let’s talk about it and learn from each other’s experiences ! |